August, 2020

Photo album here

Preface

After Yosemite, I had the singular goal of hiking in the mountains without chest pain.

It seemed like it should be easy. After all, I can do all manner of things at sea level without issue–on a bike or on my feet, I can try to make my chest explode in various ways–and it functions sublimely.

But then I go up to altitude, and it all falls apart. I become a sluggish, coughing, chest-pained wreck.

I decided to start by trying to fix the cough. Maybe the cough is causing the chest pain. Maybe fixing the cough will fix it all.

It is not a bad cough; it is just a spasm after I exhale. I tried to fix the cough already:

“Use an inhaler. It will provide instant relief,” said every doctor ever. But the inhaler did not.

The cough sometimes develops at sea level, when the air is cold. So maybe the cough is an irritation. Cold, dry, mountain air, being dragged remorselessly across the sensitive, moist alveoli in my lungs. Maybe I am desiccating my poor alveoli. Maybe I have really strong calves, but fragile alveoli.

So what do I do? I thought about wearing a mask to humidify and warm what I breathe, but that seemed ridiculous. I wasn’t sure it would be effective, but I was sure it would suck. We spend enough time in masks these days–I didn’t fantasize about wearing one whilst miles from the nearest soul.

Next I thought about my nose. What if I breathed through my nose? That would put a lot of warm tissue in between the universe and my alveoli. Maybe that could warm and humidify the air?

I started researching nose breathing, and pretty soon, it emerged as a very promising thing to try. I dove into the literature, and discovered that perhaps there is a forgotten magic in nasal breathing. I read James Nestor’s book Breathe, and it described how nasal breathing might fix not only this, but every virtually every other of western society’s woes.

But to transform was going to be a bit of work. On my side was the fact that I was, functionally, already a nose-breather. I breathe through my nose 95% of the time during the day, and (I assume) while I sleep.

However, I NEVER breathe through my nose when I exercise.

I know this, because a few years ago I came across one way of determining your easy running pace: to breathe through your nose. However fast you can run–that’s your easy pace. I tried this, and it was awful–my easy pace was barely a jog, according to this method, and mere existence was unbearable after a few minutes: violently sucking air through minuscule nasal orifices, while that gaping mouth went unused below. It made no sense.

I was committed to trying again, this time with the goal of resolving my mountain cough. Yet before I went backpacking for several days–before I tried to do this for twelve hours a day, at altitude–I figured I better be able to jog comfortably at sea level. And so, a bit of training was in order.

On the first day, I ran four miles at a 9:20/mi pace, breathing entirely through my nose. It was awful, just like before. I stuck it out, but when I finished, my head throbbed terribly. It was worse than a migraine. It was as though someone had covered a drill bit in jalapeno seeds, then reamed out each nostril.

Not to be deterred by a little suffering, I ran again the next day. This time I managed a 9:10/mi pace, but it was just as painful when I was done with the same four miles.

The next day my pace dropped to 8:20/mi, but the suffering was there waiting for me when I was done, again. I was not sure my gains in pace were worth the suffering.

The next day was when it changed. My pace dropped to 7:30/mi, and all of a sudden, the suffering was gone. It wasn’t easy easy, but it wasn’t that hard, either. I ran an extra mile, and when I was done, I felt fine.

The next day I added a little more distance, and a few more hills. My pace dropped again to 7:15/mi, and the suffering remained absent. That was it. I was now a nose-breathing runner.

The metamorphosis was shockingly quick. I expected to need weeks, but whatever adaptations my body needed to make, they were fast. If it weren’t for the mountain air, I’m not sure nose breathing would make any sense for me, despite what Nestor preaches. But I had a very specific goal–humidifying and warming the air that reaches my meager alveoli–and now I had a tool that might help.

I came up with other things to try, too–a long phone call with friend and retired doctor Amy pointed to a number of possible causes and cures. Near the top of her list was heartburn.

“Could it be heartburn?” she asked, innocently enough.

I pictured the heaping pile of Fritos and Slim Jims that I tend to consume while on trips like these.

“It’s not impossible…” I trailed off.

So, there will be Tums this time. And some periodic back stretches, in case it’s tightness in the upper back.

With this peppery blast of potential solutions identified for my chest woes, I turned my attention to my ankle.

On my last trip, I sprained my ankle. Or so I thought. Unfortunately, in the couple weeks that had passed since then, it became pretty clear that my ankle wasn’t recovering. I could obviously run on it, but it remained extremely sensitive to even a light tap on that big bone that sticks out on the inside of our ankles–the medial malleolus. Two days before this trip, I had a Zoom consult with an urgent care doc:

“What do you think?” I ask.

“We could X-ray it. Could you come in?”

I hesitate.

“I’m supposed to leave tomorrow, and I need to pack…” I trail off, as I seem to do with doctors. “If it’s broken, what would you tell me to do?”

“To stay off it. We’d probably need to get you in a boot.”

“And if it isn’t, what you say?”

“To stay off it until there’s no pain when you walk.”

I struggle with these answers, because my plans do not involve staying off of it, fracture or no fracture.

She senses my hesitation.

“Look, if you can just come in to pick up a boot, you could backpack in that. You can walk in those. They’re plastic on the bottom, so the traction isn’t great, but it would work.”

I picture myself hopping across a talus field, with one foot in such a boot. I land on a tilted slab, and my foot slips from beneath me, the smooth plastic boot sliding across the polished granite, I tumble, striking my forehead on the corner of an adjacent boulder as I fall. The scene fades to black.

“The boot won’t work for me.” I say. I cut to the chase: “If I go, and it’s broken, how likely am I to cause serious, long-lasting damage, if I’m smart about it–if I stop if it becomes painful?”

“Not likely. It will probably be self-limiting.”

I nod. I’m familiar with the phrase self-limiting, and am pleased to hear it. In doctor lingo, “self-limiting” means “go ahead, idiot.”

So that’s that.

“Just don’t twist it again,” she adds. “That would be catastrophic.”

Ok. I’ll just step carefully, then.

My fragile collection of organs begins an adventure

I leave the bay area at 8pm, as I have become wont to do.

I am SEKI-bound; I have a Copper Creek permit. I do not know what my route will entail–I have gobs of options, but just as many question marks about health.

I catnap in my car just outside SEKI. It’s a wonderful night. The forest is dark and still and warm. I gaze down at the glow Fresno, some 5,000 feet below as I sup on string cheese and cookies.

I wake myself after several hours. It is still dark. I sip now-cold espresso as I complete the drive, winding along dark park roads; down down down. I have done this before; it is all part of the happy pattern.

I do final things in the parking lot before embarking. As I am doing these, another hiker starts up the switchbacks on the Copper Creek trail. His pack is an Ultimate Directions Fastpack–he is one of my brethren; or would-be brethren, were I operating in normal modes today. I watch him and feel a tiny pang of sadness–he is hiking fast. Normal Adam would still catch up to him, because very few hike faster than Normal Adam, especially those he is unwittingly trying to catch up to.

But, today will be different. I will be going slow today. REALLY slow. Slower than I did in Yosemite. All of my air will be coming via nasal passages today, and I strongly, strongly suspect that this–combined with the thin mountain air–will mean that I am very, very slow. This should be fine. But there is still the tiny pang of sadness.

It is a silly sadness to feel. My goal is to be healthy, not fast, and I’m at the point of acknowledging that perhaps I cannot be both. But I’ve done fast, and recently that has led to not healthy; those trips ended quickly and with regret.

I begin up the switchbacks, at an intentionally slow pace, my breath methodically WHOOSHing deeply into nostrils and lungs, then out. In, then out. In, then out. I reach a calm, rhythmic stasis, and settle into the climb.

I zone out as I proceed upwards, retreating into happy thoughts on the mindless, mellow climb that I’ve done so many times before.

Above Upper Tent Meadow, I spy a hiker ahead. I see the green Ultimate Directions pack, and I know immediately who it is. I am surprised that I have closed the gap between us. Though it is difficult, I resist the temptation to attempt to catch up. I stay at nose-pace, and continue along. But I can’t stop my brain from assessing whether or not he’s getting closer, and pretty soon, it’s obvious that I’m catching up.

After a few more switchbacks, I am upon him. I pass him, at first, with only a brief exchange of pleasantries. But then there are descending hikers to pass, and as I leave the trail for them to pass, he catches up. This time, we chat for longer.

He is Ted. He is fastpacking for the first time. In fact, he is fastpacking for the first time on the loop that I fastpacked for the first time on–Copper Creek, Granite Pass, to Palisade Creek; then Mather and Pinchot Passes, and finally back to Roads End, either via Glen Pass or Paradise Valley, depending on one’s state. Ted is planning on doing this in three days, just like I did. I offer him words of encouragement, but he doesn’t really need them; he has serious cred in the running department: He’s the owner of San Francisco Running Company, and has numerous 100 mile trail races under his belt.

The next thousand feet go by quickly, as we chat about topics that are near and dear to our reasonably-athletic hearts. I explain my ankle and my chest.

“You’re not going that slow,” he comments, with a touch of disdain.

I glance at my watch. I’m about a half hour behind my typical pace. This is good; I’m walking the walk.

Soon, I abandon the trail–I am Grouse Lake bound. I may be of questionable health, but it is not questionable enough to resign myself to trails. I take a different way than I usually take, and discover a well-worn use trail. I follow the use trail. It is far easier than the way I usually take. Was always here? Or, is it a sign of Sierra High Route overuse?

As I move along the use trail, I see a hiker ahead, and I pause to chat.

He is finishing a seven day outing, and is headed back to Roads End. He went some places that I have been before, and might go this time.

“There’s a bunch of fisherman at Grouse Lake. If you do stop there, you won’t be lonely.”

I relax on the shore of Grouse Lake, watching backpackers on the opposite shore packing up. I wonder if they are the fishermen. Fisherpeople? It’s tricky these days.

I take stock of my situation–my ankle has been a tad sore, but if anything has been improving, not getting worse. I’m succeeding at going slow, and succeeding at nose-breathing, and there are no signs of cardiac woes. I conclude that this is the Universe’s approval to go further. With restrained optimism, I allow myself to ponder what adventures I might have on this trip.

The next several miles are wonderful cross-country miles along the Cirque Crest. They have a surprisingly remote feel, given their proximity to the trailhead. They are delightful, as they always are.

Grouse Lake Pass, then Goat Crest Saddle; I descend an alternate way off of Goat Crest Saddle, because Adventure!, or something, and I circle Upper Glacier Lake on the opposite side that I have in the past. It affords a slightly different vantage; one that unfortunately gives up the infinity-pool view across the lake.

I descend to Lower Glacier Lake, then descend the cliffy terrain below that. I do as I have in the past; I charge straight ahead without any consideration. Soon I am strolling through the meadows below.

So confident in my navigation, I eschew a use trail that I cross several times. Unfortunately, my confidence is misplaced–I soon realize that my last eschewing of that use trail was actually the eschewing of the trail I am trying to intersect. I contour, and find the trail once again.

I realize that for some reason, the decision to force myself to ignore pace and move slow has similarly caused me to abandon any navigational focus. It is a curious side-effect, but I suppose it is fine–I am in no hurry, after all.

At the shore of Upper State Lake, I pause again, to snack, and lounge by the lake shore. This was another potential stopping point for they day, but the day is young–too young. I will stop early, but right now, it is only 12:30pm.

As I wander amongst the Horseshoe Lakes, I am lost in my thoughts. I head towards what I believe to be the isthmus I must traverse, only to discover that it is not. I realize this when I arrive at an unfamiliar lake shore. I haven’t consulted a map in a while; these are the consequences. But the error is not a significant one; I’ve visited a new lake–although, I observe that it is admittedly fairly nondescript.

Gray Pass affords its characteristic spectacular scenery. My efforts to proceed are a punctuated by a staccato of pauses, as I stop to absorb the immense views across the Middle Fork Kings. It is a still, windless day, and when I pause, the silence is overpowering. Something about this experience–the lonely, silent grandeur–is acutely fulfilling. If I turned around now, the trip would be worth it. Of course, I’m not giving that much consideration. Things are going well, knock on Foxtail.

I reach the South Fork Cartridge Creek, and decide that this will be home for the night. In the back of my mind, I wonder what I am going to do with the time–it is only 3:30pm. It will be light for another six hours. Normal Adam would never stop here, but it isn’t just chest and ankle woes that have convinced me to stop–I’d like to climb nearby Marion Peak, but I know that trying to squeeze that into this evening would be a dubious choice. Like so many peaks I’ve cavalierly written into my plans, this one too would be passed by if I continued; written off because I was unwilling to slightly modify my agenda to prioritize such a thing.

This year, I’m taking a different tact–one with layover afternoons and early ascents, rather than evening fly-bys with shrugs.

My layover afternoon on Cartridge Creek is spent enjoyably. I have a new tent–a Tarptent ProTrail Li. I’ve been a tarp and bivy user for the last eight years, but I’ve finally relented–I guess I spent one too many afternoons curled into Just The Right Shape seeking shelter beneath my Hexamid, and I want a little luxury.

The ProTrail Li, on paper, offers it all for the gram-minded, simplicity aficionado: a minimalist shaped tarp with DCF construction; it provides full mosquito protection while pitching with just with four stakes, and can pitch just dandy with my 125 cm fixed-length poles. All in–stuff sack, stakes and guy lines included–mine weighs 17.58 oz.

Of course, it is a shaped tarp, and like most shaped tarps, it takes a bit of practice to get a good pitch. I spend some of my afternoon doing this.

I spend some my afternoon just sitting on the rocks, staring at my surroundings, fantastic as they are: immediately in the foreground lie the imposing Windy Cliffs, rising above the South Fork Cartridge Creek as it tumbles down to meet the Middle Fork Kings. Further in the distance my view is rimmed by the Black Divide, and the Sierra crest west of Bishop Pass. I can’t pick out many of the summits, but PeakFinder AR on my phone makes short work of it.

I spend some of my afternoon laying against the rocks, reading Lonesome Dove on my phone. The horse encounter in Yosemite last month made me nostalgic.

And, I spend some time simply wandering around. Not in a very curious exploratory way, just … owed to an absence of anything else to do. Six hours, you see, is really quite a long time for me to be stationary.

Evening rolls in. Sunset is gorgeous, and then a chill settles, and I tuck in for the night.

As I climb into my tent, I’m comforted by the realization that I have no sign of any chest discomfort, and no cough, either. I’ve been pretty religious about not only breathing through my nose, but also taking a puff on an inhaler and an Aspirin every four hours. I have no idea which of these is the most helpful, but I’m thankful the combination appears to have worked.

I take off my “ankle protector” that my wife fashioned for me — a Smartwool sock that has had the foot cutoff, and an elastic strap sewed to it, to keep it in place over my malleolus. When I wear it, I double the Smartwool part over on itself, to provide padding. The idea is to provide some de minimus protection for that obviously still-quite-sensitive bone. Either the protector has worked, or I’m just lucky–my ankle seems to be doing just fine.

All in all, I decide that I’m quite enjoying myself. It was a trip without lofty expectations, but so far, it has been a resounding success. I am quite alone, quite happy, and in good health, in one of my favorite corners of the world.

Though I am content and comfortable, I sleep poorly.

I am up, and then I am ascending White Pass. I have never ascended White Pass on fresh legs before–it is a pleasant change.

Soon I am atop it, and from here, I look upwards along the ridge line leading to Marion Peak, which departs White Pass to the north. It looks a tad foreboding. It isn’t enough to deter me, and so then I am off. Immediately, the climbing is fun–a hands-and-feet affair with mostly minimal exposure. In a few places, the exposure is greater, and is what I consider unabashed third class. In those moments, I catch myself breathing through my mouth–the first times on this trip.

My progress is slow owed to the technical terrain, but the time flies, and soon, I arrive at the summit. I linger here for quite a while; the views are as good as I had imagined.

The summit register reveals a surprise: Even with its proximity to Roper’s route, Marion Peak is rarely climbed. Six parties climbed it in 2019; I am the first of 2020.

As I sit amongst the turrets on Marion Peak’s summit, I grapple with what to do next. The truth is that I hadn’t really planned this far ahead–there were too many health uncertainties to invest time in detailed route planning. I could return the way I came, then proceed to Red Pass, Marion Lake, and Lake Basin. Of course, I’ve done that before. But the real object of allure at the moment isn’t in that direction: It’s north of me. It’s Arrow Peak. I’ve been skunked by Arrow Peak several times before. Never for a particularly good reason, save for a sprained ankle in 2018. Every other time was a half-hearted attempt; a peak written into the margins of an itinerary that had no room for it. I decide that I’d like to camp below it tonight, to give it a full-hearted attempt tomorrow.

Still, there are several ways to get there, and from those I must choose. I decide that the climbing along the ridge was fun, and my ankle didn’t seem to mind–I want to do more of that. In that spirit, I depart the summit to the northeast, along the ridge top of the Cirque Crest, towards Mount Ruskin, which is a couple miles distant. If things go well, and if I’m making good time, I’ll climb Ruskin this afternoon.

As I near the lakes below Cartridge Pass, I make my decision: I’m not climbing Ruskin today. For the most part, there was nothing challenging about the two-mile ridge top traverse to arrive here, but the final descent from the ridge features never-ending talus that has my ankle complaining quite vocally. I suppose it is one thing to climb talus on an ankle like this, but another thing to descend it. As I descend the talus, I glance up periodically towards my destination; it never nears, there is always just the infinite talus. I ponder the surface area of the talus field. I suppose that it is something like a fractal, or quantum foam–maybe you need more than 3 dimensions to describe it. But maybe there is some coordinate system in which the surface of the talus is fundamentally smooth–maybe when you have talus zen infinity, you recognize that. Talus dullards can’t even discuss it meaningfully; it would be like a dog describing electromagnetism–we don’t even have the right words in our language, because we cannot interact with it. But maybe those who have reached talus nirvana can; it is obvious, and they happily *skate* along parameterized curves in *talus space* that the rest of us can’t see. It is a straight path in *talus space*, but a complex jagged topography to the rest of us. If I keep at this, I think wistfully, maybe some day, I will be able to *sniff* *talus space*.

By the time I conclude my inane mental meandering, I’ve arrived at the shore of a lake; it is on off-trail gem that is probably infrequently visited owed to its isolation from everything, save for the Cartridge Pass trail, which in itself is not an enormously popular thing. I will give this lake the attention that it deserves–I am ready for a break. I’m relieved by my conclusive decision to abandon Ruskin for the day; I glance upwards at it–it looks cliffy–even if I could *sniff*, it might not help. It is not what my ankle nor chest ordered.

However, a leisurely dip in this lonely, abandoned lake, is a prescription I’m happy to follow.

I strip in the hot afternoon sun, and exhale slowly as I descend into the icy water. I look skyward in a moment of humbling gratitude. There is not an ounce of stress, anxiety, or pressure in my body. It is not talus nirvana, but it is a nirvana, of sorts.

I make speedy progress on the remnants of the Cartridge Pass trail, as I descend towards the South Fork Kings. I’ve decided that I’ll cross the Kings, then head up the talus wall towards Bench Lake. I’ve climbed it before, and it was fun–I think my ankle is up for ascending talus.

I cross the river, and wander along the base of the talus until I decide that no spot seems preferable to any other to begin an ascent from. I begin upwards.

My memories prove true; the climbing is fun, and shortly, I arrive at the shores of Bench Lake.

I snack by the shore, and am struck with the realization that it’s been quite some time since I encountered anyone. There was Ted–who else was there? Ah, the fishermen, yes. I saw the fishermen yesterday. That was … I glance at my watch … about 30 hours ago.

I eat while I walk, as I circle Bench Lake on the unusual luxury of a trail. One advantage of nose-breathing is that eating while walking at altitude doesn’t require the continual gamble of “chewing” vs “breathing” — a gamble I’ve come close to losing on more than one occasion.

Soon, I depart the trail, and negotiate the mild cross country leading to the basin below Arrow Peak. It begins raining before I arrive, but it is a gentle sprinkle without nefarious intent.

I set up my tent, and relax, enjoying an early stop for the day once again. I spend the next few hours watching the evening light expend itself against the rock that surrounds this basin, and the waning clouds above. Life is good.

I am up and moving early. It is Arrow Peak Day, lest the mountain gods bestow a surprising skunk upon me. The weather is clear and my body is cooperating, so upwards I go.

The ascent is straightforward, and in two hours I am atop the summit. I am somewhat surprised by haze–it must be wild fire smoke.

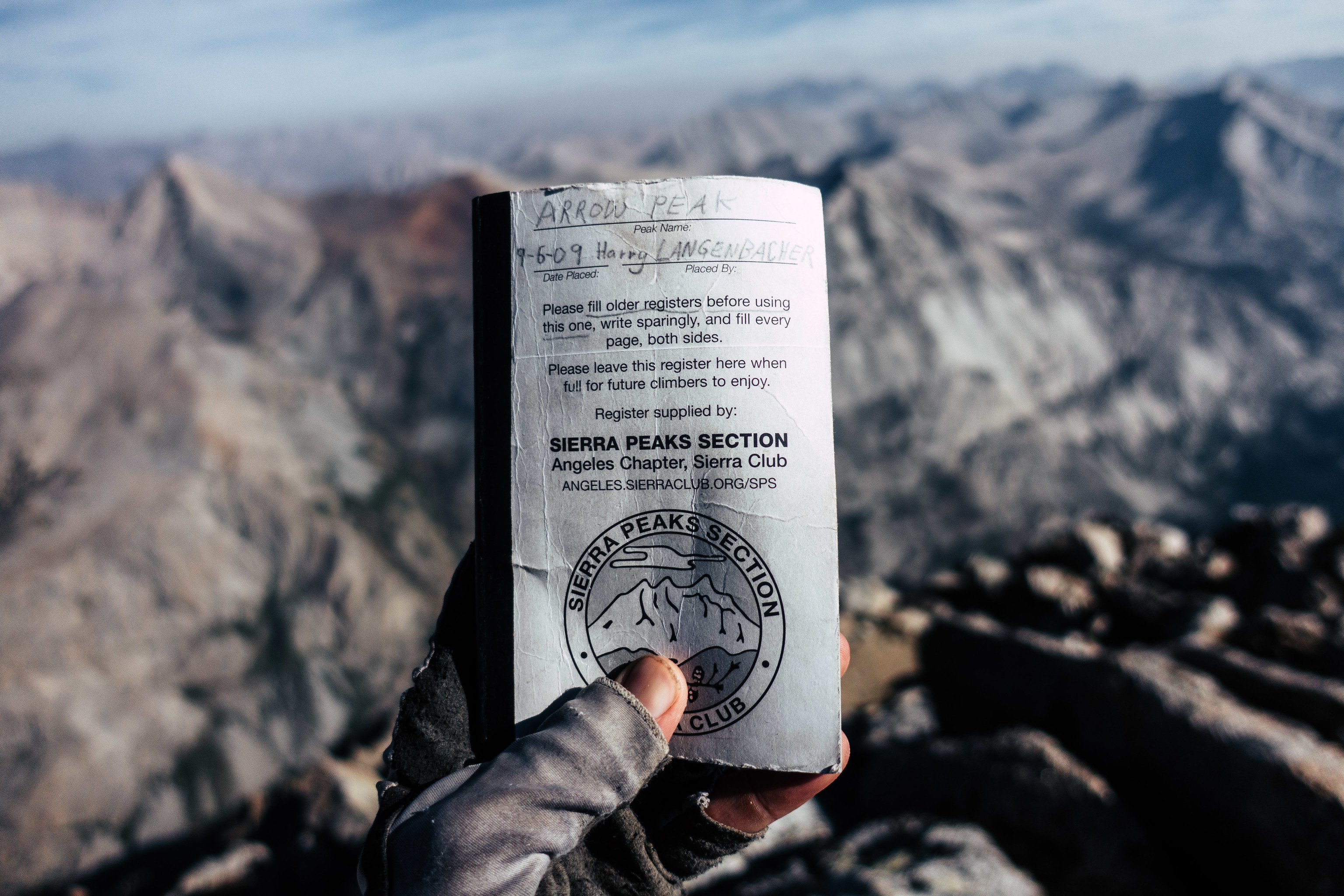

I take my time paging through the registry. I discover the entries from my would-be companions in 2018–and many, many more. Arrow Peak is fairly popular, despite its relatively isolation. I do note that I am only the sixth to summit this year.

I linger for 45 minutes, savoring the vista. That Arrow Peak commands such a view should not be a surprise; it is visible from many places, and consequently, many places are visible from it. I particularly enjoy the views to the north and east–the Palisades, Bench Lake, Taboose Pass, and much, much more. Marion lies directly across the South Fork Kings, which carves out the Muro Blanco just to the north of me.

The descent is easy, owed to judicious selection of scree chutes that I spotted on the way up. As I near the basin below, I angle southward. I need to climb the massive ridge that I stared at all evening prior; it separates me from trails, trailheads, and my car, all of which I must now think about returning to.

I have climbed this ridge before. In fact, I have climbed it in a few different ways. I take yet another way today–it is neither the easiest nor the most difficult, but it does reward me with access to a minor summit along the ridge–a summit that has called to me before, but that I have neglected.

Today I scramble to the summit. The views from here–though not markedly different from Arrow Peak–were well worth the climb. Unsurprisingly, I cannot find a summit register.

I sit on my laurels again, snacking and gazing.

Down, down, down.

The going is easy and my ankle doesn’t argue. I pause frequently to take in the view–one of my favorite in the Sierra; Rae Lakes, Fin Dome and Painted Lady; Cotter, Gardiner and Clarence King are there staring back at me.

My mind begins to wander. I am enthusiastic that–this far–I seem to have avoided the chest discomfort that plagued my recent trips. Perhaps it was one of the 18 things I tried to mitigate it–or perhaps its an ailment that has simply vanished as ailments sometimes do. I am indifferent to which it is, but am thankful that it is the case.

I emerge onto the JMT. I turn westward on it, descending towards Woods Creek crossing. Within minutes, I pass a couple–we exchange a brief greeting. They don’t know that they’re the first people I’ve seen in … 54 hours? Amazingly, I’m not all that chatty.

What I lack in social ambition I make up for in hunger; I pause along Woods Creek, below the suspension bridge, for a snack. I am slightly dismayed to discover that I am running a bit short on food. I briefly debate heading down Paradise Valley–the short way back to the car; only 16 miles or so from here. But I decide against it. I still have a few thousand calories. I’m willing to trade a bit of potential hunger for another serving of the high country. I cross the suspension bridge, and hike onward, towards Dollar Lake.

I pass Dollar, then Arrowhead Lake, before weather erupts above me. The distant rumble of thunder turns into sharp cracks just above. I happen to be looking at Fin Dome when I see an obvious direct strike. This is enough data to suggest that I probably shouldn’t plan on going over Glen Pass tonight. This is fine–it’s already 5:45pm. If I’m going to stay true to the spirit of this trip, I probably shouldn’t be descending Glen Pass by headlamp.

I decide to head towards Middle Rae Lake. As I near it, I spot a handwritten note attached to a trail sign:

WINDS MAY EXCEED 50 MPH TONIGHT–PLEASE TAKE SHELTER!

– RAE LAKES RANGER

Well, that seems like a good test for my new tent.

I find a sheltered spot, and pitch my tent, then climb inside. It’s too early to sit around doing nothing in a tent, but the weather hasn’t abated, so my choices are limited.

I snack, and count my calories more carefully. I have around 1,800 calories left. That sounds like a lot, but I eat like an Olympic swimmer. 1,800 calories is a around half of what I eat on a typical backpacking day. I decide that some minor rationing is needed, and without any advanced calculus, eat a few hundred calories, then toss the rest back into my bear can.

The weather continues for an hour, and then relents. The rain ceases, and the wind abates. I am disappointed that my tent will not get the test I was hoping for.

I climb towards Glen Pass at a nose-comfortable pace. It has become my new governor. Which is not that bad, really.

I’m on top in under an hour. I enjoy the view from the top. There is something about Glen Pass for me; I have been here a dozen times or so. On most of those visits, I was either embarking upon an adventure, or finishing one–more often the latter. It’s usually around here that I say goodbye to the High Sierra. There are a few more glimpses of it on the descent–West Vidette, then Mount Brewer–but nothing like this vista.

As I stare wistfully into space, the half dozen hikers I passed on the ascent join me. We chat about hiker things, which is really quite nice, since I haven’t exchanged more than a few sentences with anyone since Ted, 72 hours ago.

This is a lively bunch; a family, with highschoolers, and maybe a grandpa, but I’m not bold enough to ask. They were out for five days, and are on their way out, via Kearsarge Pass. Yesterday, they climbed Mt Cotter.

“It doesn’t look so impressive from this angle,” comments the son.

We talk about my trip, and then more important things, like sausages; I refer them to Lockeford Meats which is surely just as much of a bucket list item as any Sierra summit (grand as Sierra summits are).

Eventually, I bid them adieu, and embrace the beginnings of the 7,000 foot descent to Roads End. I move quickly; one advantage of my lean caloric planning is that my pack weighs nothing–surely under 10 lbs.

Down, down, down. I move quickly, but carefully–I have been watching every step for the last 50 miles and I don’t intend to err now.

Above Junction Meadow, I am stopped by a hiker.

“There’s a rattlesnake ahead!” She says with excitement. “I’m letting people know.”

I nod. As a denizen of the East Bay, I am no stranger to rattlesnakes.

I proceed, and verily, there is a rattlesnake, coiled on a nearby rock. It is not aroused by our presence. More hikers come along as I am looking at the rattlesnake. It is a curious but not unheard of thing, to see a rattlesnake at 8,000 feet.

Soon, there is Charlotte Dome, and eventually, the Sphinx. Finally, there are the final switchbacks. I am jogging now. I pass many people. Most of them look surprised. I think it is the sight of someone jogging around here.

I reach the Bailey Bridge, and there is no contemplation needed; I strip down and enter the rushing South Fork Kings. It is cold, but my funk is probably incredible. It must be right? You never seem to know about funk, when its yours. I submerge, and am hit with the usual sensations of a cold-water plunge: simultaneous panic and relief.

I dress on the shore, and cross the Bailey Bridge. As I do so, a man stops me. He had been glancing at me periodically, in the way that someone observes someone who doesn’t want the observee to notice.

“Were you backpacking?” he asks.

“Yeah, a few days.”

“Wow. I’ve always wanted to do that.”

“Go. You should go. It’s spectacular. It’s life-changing up there.” And then I shake my head. I don’t have the words to explain, I know that. But there are people–people whose lives are void of mountains. And I can’t imagine it. I mean, I had no mountains in my life until my mid-twenties. But my god! I live and breathe them now; they motivate me and feed me. What would life be, without mountains? Of course, it would be okay; people can live and die and generations can come and go. But it would be flat. Maybe like, a world without music? Or cheese? Something like that.

“Maybe I will go backpacking,” he says, as I pass him.

Then, I am on the two mile sandy walk. Today, it is a two mile sandy jog, albeit a mellow, slow one. I squish along at a 10:00 per mile pace in the hot sand, with my pack bouncing along. I ate my last calories–a Slim Jim and some Frito crumbs–at the Bailey Bridge. I’m still hungry, but not famished.

I usually use this stretch to ponder Deep Thoughts about a trip. Today, I’m pretty void of them–but I am saturated with gratitude. This entire trip was one that I was prepared to have cut short on day one, by a spasming, achy chest, or an ankle that was going to have none of this. Instead, I had an adventure–a gorgeous, remote, spectacular, adventure. I had my favorite corner of earth all to myself. I climbed new peaks and passes, and visited old friends. I adhered to a regimen that’s typically difficult for me–taking things slow and easy–and maybe it worked, or maybe it was something else. In the end, our bodies’ are consumables–we don’t get to keep doing the things we want to do, just because we want to do them–and we will all reach a point where doing things like scrambling around the High Sierra are no longer things we can do. That day will come, but I’m grateful that it isn’t upon me yet.

Soon, I’m at my car. I gorge on the food that I left in the bear box, then gorge again as I leave the park, celebrating with a cheeseburger at the Kings Canyon food court. It’s an outside affair, but even so everyone is wearing a mask, so I don mine. This is evidence that COVID didn’t get eradicated while I was out.

Oh well. I suppose no trip is perfect.

Wonderful trip report and great route. Thanks for taking the time to write it up and share. I love the moment when you tell that gentleman that he should backpack sometime. I hope he does. I was hoping to climb Arrow Peak in 2020. I hiked past it when the Creek Fire was raging. I couldn’t even see the peak from Upper Basin as I hiked through the area. I took a picture of the trail junction and told myself – I will come back.

Thanks Doug! I had the same experience walking past Seven Gables during the Creek Fire. The visibility wasn’t so bad that I couldn’t see the summit, but it was bad enough that I thought summit views would be squandered. I climbed some nearby minor summits instead. I hope you get your chance at Arrow Peak!

As mentioned on HSTopix, one of the most enjoyable trip reports ever.

Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for the comment Bill–glad you enjoyed it!